Game Design

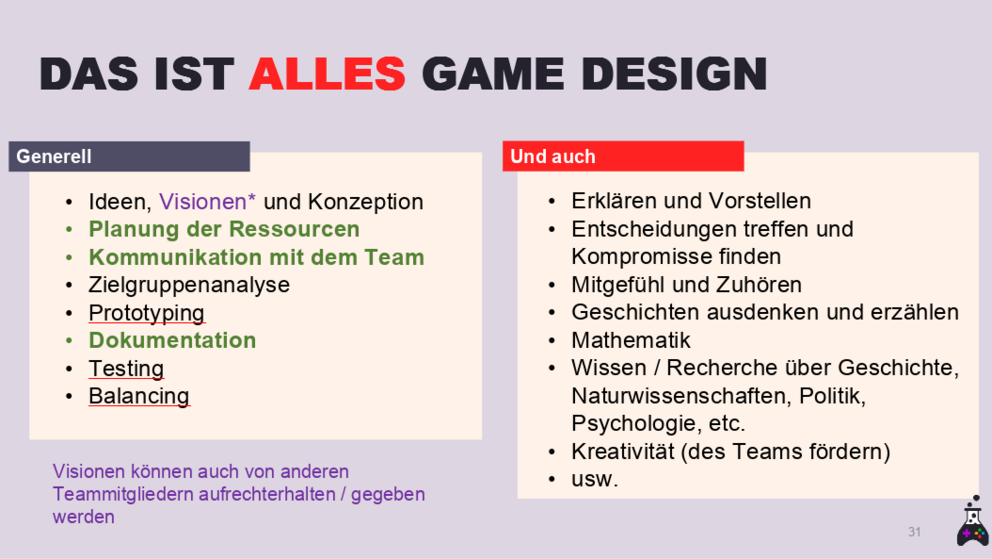

Game Designers create games in theoretical form and guide their team to bring the vision of each game to life. In the workshops you will learn conception, level design and how to write a game design document. As well as communication, team leadership and project management. To take part in this workshop, you must have previous experience in game development. It is often enough to have taken part in this seminar in another area at least once.

Skills in the Game Design Department

Our role and responsibilities

In the winter semester, the role of game designer is experienced in its entirety for the first time in the GameJam. This is where all the workshop content and exercises for effective realisation come together in a small time frame. Game designers have to lead an unfamiliar and as yet inexperienced team for the first time and utilise the creativity of their team effectively in a short period of time. They lead the joint conceptualisation and decisions regarding gameplay, mechanics, etc. and later work actively in Unity to put the game together.

If you take part again in the summer semester, you will apply the knowledge you have learnt in the semester project. Here, the responsibilities of a team lead are added over a long period of time. This means, for example, project management tasks such as organising and holding weekly meetings, resource management, creating or adhering to a production plan and all media production tasks such as integrating assets into Unity or writing the game story and carrying out the narrative design.

Vocabulary of the Game Design Department

Project management (PM) includes many different aspects, such as resources (time, people, materials, premises, etc.), but also aspects relating to communication and decisions (e.g. protocols) or documentation of knowledge (e.g. wikis). Other components of PM can also include the following questions: How are tasks sensibly distributed and stored in an accessible way, e.g. with Kanban? How do you organise the sharing of files and set up a folder and project structure that makes sense for the project?

In the context of game development, mechanics are rules that describe main features. They can describe abilities, but also represent circumstances in the game world and reflect recurring rules of the game. By "core mechanics" we often mean character-defining mechanics for a game. These define the gameplay, the functions or the possible actions of the person playing the game.

An example: In Tetris, a core mechanic of the environment is that new blocks continuously fall onto the playing field in a certain rhythm. The "turning" of the blocks turns out to be a core mechanic for the possible actions.

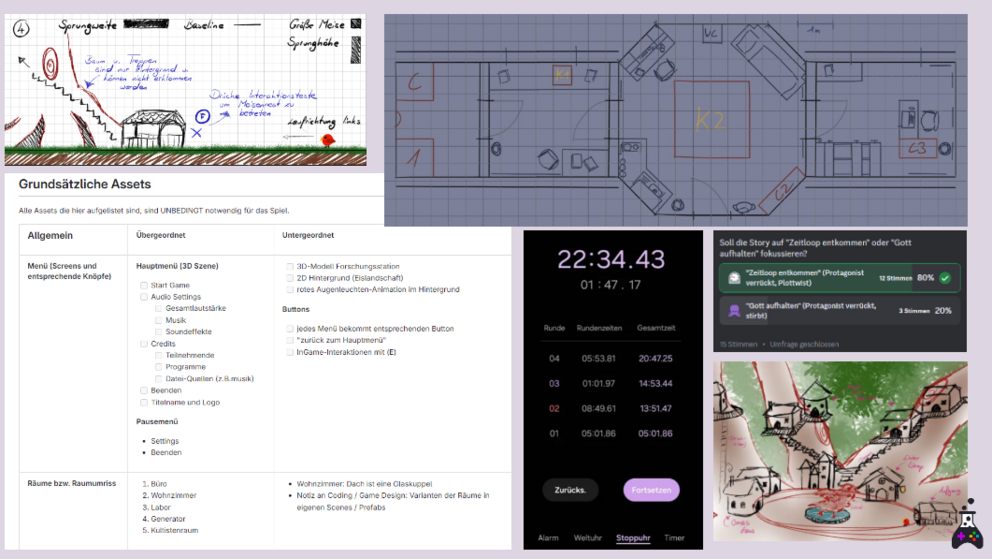

It is important to estimate the scope of a prototype fairly and with enough buffer time.

To develop a prototype, you need the resources of time as well as people and their skills. If a game prototype is out of scope; because the idea is too broad, the production team is in danger of overloading itself. The project could fail, for example due to a lack of human resources. This and other problems should be avoided through good scoping.

Paper prototyping describes the process of testing a game concept and its mechanics on paper before going into production.

The principle is often used in physical table top games (board games), but it also helps in digital game production to physically test with pen and paper whether the concept works or not.You can already test scaling, i.e. proportions, and also mechanics.

Whiteboxing describes a process in which simple white boxes are placed in a level in order to visualise it first.

This involves building out a level completely with placeholder objects so that everyone involved gets a good spatial idea of the level. Later on, the whiteboxing is then used as a template and can be used to decorate the real level with 3D models or 2D assets.

Quick Navigation